Command Line

The command line is a text interface on a computing system into which we type commands to tell the computer what to do. In times past this would be done via a dedicated monitor and keyboard combination called a terminal. This has been replaced with a program that emulates these old system and provides us a window into which we can type.

The command line program that we will be learning is the Bash shell. It is the descendant of a long line of shell programs, and it is specialized to help us manipulate our file, start programs, and automate tasks involving these things. It is also the only way to run jobs on the Canadian supercomputers.

I will be demonstrating everything on the supercomputers in order to help you become more familiar with them. Almost everything in this course does not require the supercomputers though, so there is no need for you to use them unless you would like the practice.

Under both Linux and Mac OS X, you can start up a Bash command line session by starting a terminal program (search for terminal in your applications menu). The default command line interface in Windows is the older Command Prompt or the newer Power Shell. To use Bash you need either install the Windows Subsystem for Linux (a full Linux installation) or Cygwin (a collection of UNIX programs, including Bash, compiled for Windows).

For this course, it is sufficient to install the free version of MobaXterm (a popular with our Windows users). It includes a basic Cygwin installation along with a graphical file transfer program that lets you click-to-edit and drag-and-drop to transfer files when connected to the supercomputers. An even lighter option is to install the secure shell installable component (this requires Windows 10 or later, for earlier versions you can use the standalone PuTTY program). Then you can secure shell from the Windows Command Shell to the supercomputers and use Bash there.

MobaXterm - https://mobaxterm.mobatek.net/

Secure Shell - https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/administration/openssh/openssh_install_firstuse

PuTTY - https://www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~sgtatham/putty/latest.html

Secure Shell

The Canadian supercomputers can be access from anywhere there is internet access using the address <supercomputer>.computecanada.ca and the secure shell client suite of commands

ssh- used to run commands (secure shell)scp- used to copy files (secure copy)sftp- alternative to copy files (secure file transfer protocol)

As a demonstration of our first command, I am now going to show how to connect to the SHARCNET supercomputer graham

from a local shell session on your computer using the ssh command. Connecting to the supercomputer is not

required for this course (unless you are using Windows and haven’t installed MobaXterm), but it is required to use

the supercomputer, so it is good practice.

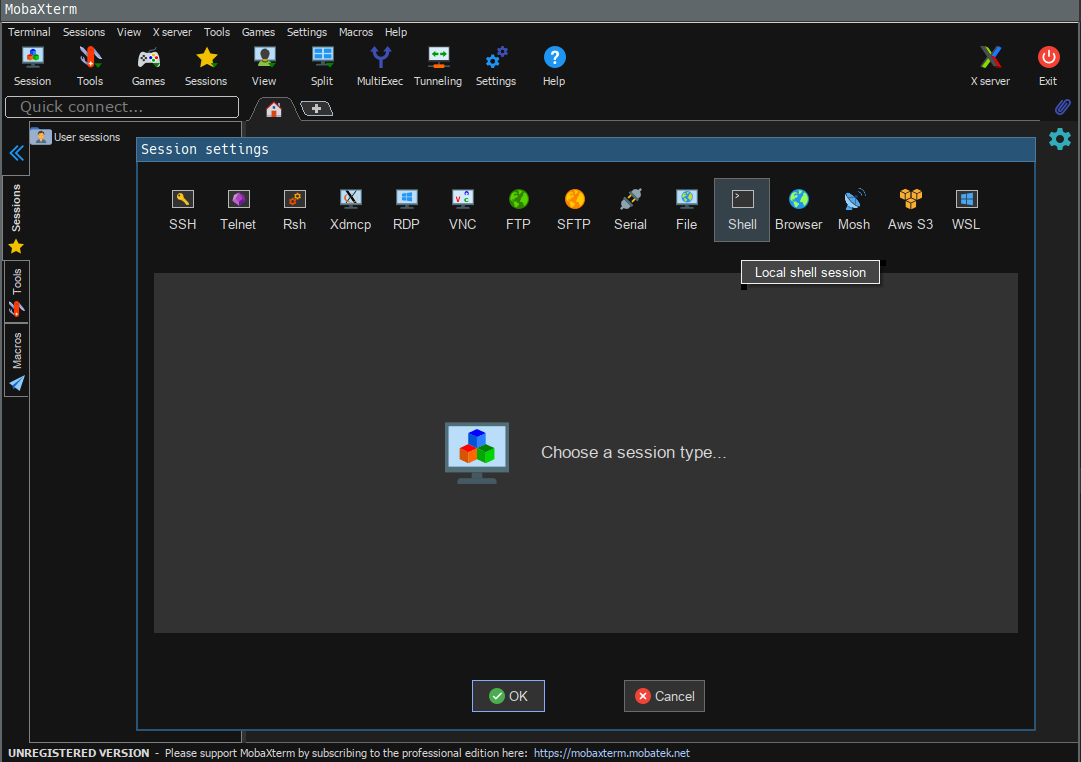

First we need to open our terminal program. For Linux and Mac OS X, the terminal program can be found by searching for terminal under the applications menu. For Windows, if you installed MobaXterm, click the Sessions icon in the upper-left, and then click the Shell icon the middle-right. If you installed the secure shell installable component, start the Command Shell under the applications menu. If you have installed PuTTY, start it.

To connect with PuTTY, we type graham.computecanada.ca into the Host Name box and then press Open. It will

then prompt for my username and password and then give us a terminal that is connected to graham and running the

bash (the default Graham shell). For all other methods we start with a terminal on our local computer running our

local shell (generally bash or a bash based derivative). The shell, which is also referred to as the command line

or the terminal, does what is known as a read-evaluate-print-loop (REPL). That is, it interacts with us by

(R)eading a command from me,

(E)valuating the command,

(P)rinting the results of the command, and

(L)ooping (reads the next command, etc.)

A Bash command is generally the name of the program to run followed by any information that program needs to be

told in order to do its thing. Assuming we aren’t running PuTTY and already connected to graham, we need to run

ssh and tell ssh to connect to graham.computecanada.ca with our graham username. So I type

[tyson@tux:~]$ ssh tyson@graham.computecanada.ca

(tyson is my graham username) and press enter. This brings us to the second step. The computer runs the ssh

command. The ssh command prompts for a password (note there are no stars when typing it in), logs into the graham

supercomputer, and starts a new command line session inside my existing one.

When we am done running commands on graham, type

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ exit

This causes the command line session on graham to complete, and, in turn, the ssh command ran on our local

computer to also completes. This brings the local computer to the loop phase, and it will then prompt for our next

command. We can enter another command for the local computer or type exit, which will cause the the local

session to also end and close the terminal application.

Data storage

Now we are going to review the basics of data storage on computers. Data is stored in a hierarchical tree

structure. For this course we will be working with some data we can download using the wget (web get)

command

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ wget https://staff.sharcnet.ca/tyson/flights.zip

You don’t need to exit from graham at the end as I did as will continue using it with our next exercise. Note also

that the Compute Canada wiki page contains details pages on using ssh, PuTTY, and MobaXterm.

or the curl command (in the event your system doesn’t have wget)

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ curl -LO https://staff.sharcnet.ca/tyson/flights.zip

We can then unpack this file using the unzip command

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ unzip flights.zip

which leaves me with this tree of files and folders (much of the details outside of the unpacked flights folder are specific to Linux and our supercomputer storage layout and will be different for your personal computer)

/

├── home

| ...

| ├── tyson

| | ├── flights.zip

| | ├── flights

| | │ ├── 0144f5b1.igc

| | │ ├── 2191bc99.igc

│ │ │ ...

│ │ ├── nearline

│ │ │ ├── def-tyson -> /nearline/6001152

│ │ │ └── def-tyson-ab -> /nearline/6023753

│ │ ├── projects

│ │ │ ├── def-tyson -> /project/6001152

│ │ │ └── def-tyson-ab -> /project/6023753

│ │ └── scratch -> /scratch/tyson

│ ...

...

├── nearine

│ ...

│ ├── 6001152

│ ├── 6023753

│ ...

...

├── project

│ ...

│ ├── 6001152

│ ├── 6023753

│ ...

...

├── scratch

│ ...

│ ├── tyson

│ ...

file - named piece of data

folder - container holding files and further folders

link - a reference to another file or folder

Before the graphical analogy to a filling system, folders were called directories, and this is reflected in the names of command line commands (e.g., change directory, print working directory, etc.), so we will use that.

To specify a piece of data, we need to specify both the file name the data is stored under and the series of directories (folders) that that filename is stored under. It isn’t sufficient to tell someone (or the computer) just the filename as they would then have to look through all the folders to find it, and they very well might find another file with the same name in a different directory (folder).

To uniquely specify a piece of data we, therefore, have to specify all the parts from the start. For example

start at the start

under the home directory

under the tyson directory

under the flights directory

the data is in the 0144f5b1.igc file

When writing this down, we separate all the components with a / and call it a path because it gives the path to follow through the directories to locate the file. A leading / says the path is absolute as it starts at the very start. The above example would be /home/tyson/flights/0144f5b1.igc.

Frequently we are only referring to files relative to some common starting point, such as the location of my person storage /home/tyson, in which case we call it a relative path and do not include the leading /. The above example would be flights/0144f5b1.igc.

When working with data on another computer, we need to specify not only the full file path to the data, but also computer it is on, and the username to use to login to that computer to get it. An example might be tyson@graham.computecanada.ca:/home/tyson/flights/0144f5b1.igc

You may be more familiar with a Windows file specifications, which would look something more like C:\Users\Tyson\Desktop\flights\0144f5b1.igc. The key difference here is that in Windows uses \ instead of / to separate the components and explicitly specifies the physical location of the storage at the start of the path with a drive letter like C:.

There are also no drive letters with Linux. The physical storage is implicit in the path. When I plugin a USB

stick, for example, a new path like /media/tyson/80BC-6336 shows up under which I can access all the files and

directories on that USB stick. The mount command can be used to view what storage is under what paths, but we

won’t be plugging any USB sticks into the supercomputers, so we will leave it at that.

Exercises

The

treecommand displays a tree view of your directories and files. Run it and see if the results are what you expect (note this command may not be available on your personal computer).

Getting around

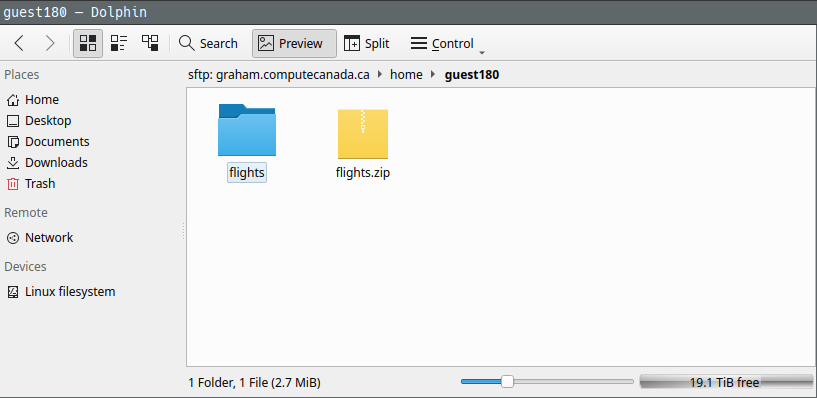

Under a GUI we navigate our folders (directories) and files with a file manager. A typical graphical file manager shows us the path of the folder we are viewing and its contents as a series of icons

Like a file manager, the command line has a directory (folder) that it is currently in. We call this the working

directory, and the pwd (print working directory) command will tell us what it is

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ pwd

/home/tyson

We so frequently want to refer to files relative to our home directory, that the command line provides ~ as

shortcut to means /home/tyson. With this information, you can see that the command line is actually configured

to tell us exactly where we are every time we enter a command. That is, [tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ is saying the

command you enter is going to run

under the user tyson

on the computer gra-login3

in the directory /home/tyson

If you become a power user with many terminals open at once, you will appreciate this information in your face every time you enter a command.

The file manager also shows us each of the files and folders (directories) in its working directory. The ls

(list) command does the same in the command line

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ ls

flights flights.zip nearline projects scratch

If we hover our mouse over a file or folder or right click and picking properties, we can get extra details about

a file or folder, such as the day it was created, its size, and the access permissions. The ls command will also

provide this information to us if we ask it to with the -l (long) switch

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ ls -l

total 2804

drwxr-xr-x 2 tyson tyson 141 Mar 1 2018 flights

-rw-r----- 1 tyson tyson 2794605 Mar 2 2018 flights.zip

drwxr-xr-x 2 root tyson 4 May 24 23:47 nearline

drwxr-xr-x 2 root tyson 4 May 24 23:47 projects

lrwxrwxrwx 1 tyson tyson 14 May 24 23:47 scratch -> /scratch/tyson

The file manage lets us open the file by double clicking on it, or right clicking and picking open with. For example,

double clicking on the flights.zip will likely open it in the zip extractor program and let us unpack it. We have

already seen how to do this with the command line when we ran the command unzip flights.zip.

The file manager also lets us go into the other folders (directories) in the current folder (working directory) by

single or double clicking on them. The command line provides a cd (change directory) command to do this. For example,

the equivalent of going into the flights folder and looking around would be

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ cd flights

[tyson@gra-login3 flights]$ pwd

/home/tyson/flights

[tyson@gra-login3 flights]$ ls

0144f5b1.igc 2191bc99.igc 4620f232.igc ...

You will note that when we moved into the flights directory, the prompt changed from ~ (the abbreviation for

/home/tyson) to flights to reflect the fact that we are now in the flights folder. In the file manager, we

can click a prior part of the path (or the back arrow) to return to where we were. The command line provides

a special folder called .. that refers to the parent folder to allow you to go back

[tyson@gra-login3 flights]$ cd ..

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ pwd

/home/tyson

This is actually baked right into the operating system, it just isn’t normally shown as files and folders that

begin with a period are not shown unless the -a (all) flag is used

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ ls -a

. .. .bash_history .bash_logout ...

It is good to know this as many time special things like configurations are stored under files or folders with a leading dot in order to not cluttering up your regular listing. You can also see there is a . in addition to the .. directory. The . directory is the directory itself. This is convenient as we frequently want to tell a command to do something to this directory (i.e., copy the files from some place to this directory).

With the file manager we could create a new folder called downloads by right clicking and picking create new ->

folder and then copy the flights.zip file to it by dragging it over and dropping it on the new downloads

folder icon. With the command line we can make a new folder with the mkdir (make directory) command and copy

the flights.zip file to it with the cp (copy) command

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ mkdir downloads

[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ cp flights.zip downloads/

where for copy like commands you generally specify one or more source followed by a destination separated by

spaces. The trailing / on the destination is optional, but it makes it unambiguous that downloads is suppose

to be a directory to a copy of the flights.zip file in. Without the trailing / the cp command determines

whether downloads is a folder to put it based on checking to see if downloads is an existing directory or not.

We have put together a quick reference guide to many of the common (and not so common) commands and options for you to refer to (see the reference link in the course index) as the goal of this course it not to put you to work memorizing a bunch of commands. The commands you frequently use will commit to your memory soon enough through regular usage without any effort on your part. You can look up the others when you need to.

Exercises

These exercises assume the following file and directory layout that exists after the previous demonstration (adjusting tyson to your username)

/

├── home

| ...

| ├── tyson

| | ├── downloads

| | | └── flights.zip

| | ├── flights.zip

| | ├── flights

| | │ ├── 0144f5b1.igc

| | │ ├── 2191bc99.igc

│ │ │ ...

│ │ ...

| ...

...

Discuss your answers and test them out to verify if you are correct or not.

The full set of options for a command can be found in the manual page. The command

man <command>(e.g.,man ls,man cp, etc.) will bring up the manual page for a command. Use the arrows and page up/down keys to scroll around,qto quit, and/<text>to search for. Using the lsmanual page, answer the following questionsa. What does the command

ls -lhdo?b. What does the command

ls -Rdo?c. How do you sort by last modified date?

Starting from /home/tyson/flights directory, which of the following commands can be used to switch to the home folder (remember .. goes the parent directory and . stays in the same place)?

a.

cd .b.

cd /c.

cd /home/tysond.

cd ..e.

cd ~f.

cd homeg.

cd ~/flightsh.

cdi.

cd ../../tysonIf

pwddisplays /home/tyson/flights, what doesls ../downloadsdisplay?a. ls: cannot access ‘../downloads’: No such file or directory

b. downloads flights flights.zip

c. 0144f5b1.igc 2191bc99.igc …

d. flights.zip

The

rmdir(remove directory) command removes a directory. Trying to remove the downloads directory gives[tyson@gra-login3 ~]$ rmdir downloads rmdir: failed to remove 'downloads': Directory not empty

This implies we have to empty the directory first with the

rm(remove) command. Fortunatelyrmhas an option that will remove everything in one go. Use the manual page to figure out the required command.How can the

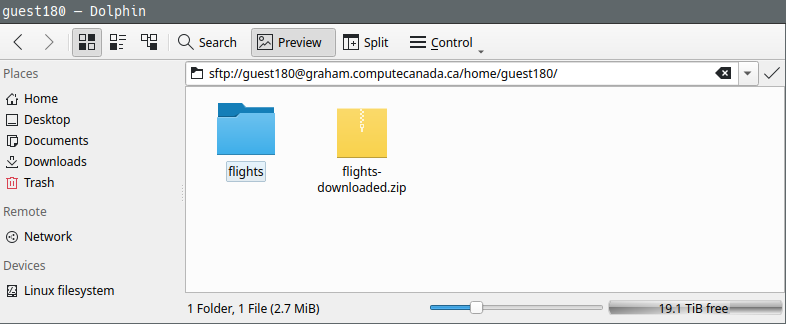

mvcommand be used to rename flights.zip in /home/tyson to flights-downloaded.zip?

Technicalities

Now that we have run some commands, and had a look at some of the manual pages, we are going to take a moment to step back discuss some of the technicalities and syntax. The command line we are using is called bash. This is an acronym for Bourne-again shell, which is a word play on the original Bourne shell from which it descended. There are many shells, including the original sh, ksh, csh, their decedents ash, bash, dash, tcsh, and the even newer zsh and fish.

The subject of what shell to use can be somewhat of an almost religious issue for some. We are learning bash as it is the most widely used and the default on most system. It is bit crufty due to its extended history, but works well. The biggest gotchas with bash is that variable expansion also undergoes word splitting and pathname expansion unless quoted. This means many people’s scripts do not properly handle filenames with spaces in them. Neither zsh, which is very compatible with bash, nor fish, which is not, have this issue.

In the command line quick reference we have stated that programs are run by specifying the command followed by the arguments separated by spaces. That is

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] <program> [argument] ...

When we write something this way, it is not something you are suppose to type in literally. Rather it is a syntax specification that tells you how to put together the required components when specifying your command. You need to replace the items in the angle and square brackets with what they describe.

That is, <program> should be replaced by the the name of the program you wish to run (e.g., ls), and

[argument] should be replaced by the argument you wish to provide to the program (e.g., -l). The difference

between the <>s and []s is that the former has to be present while the later is optional. That is, a command

must included a program to run, it does not need to include an argument. The full syntax is

<xyz>- xyz is required[xyz]- xyz is optional<xyz> ...- xyz is optionally repeated (more of the same)<xyz> | <uvw>- either xyz or uvw but not both

With this in mind, we can now see that saying the syntax for a command line is <program> [arguments] ... means a

command is a required program name followed by any number of optional arguments (including none) separated by

spaces.

Sometimes type faces or capitalization are also used to indicate what parts of a statement are suppose to be typed

exactly as is and what parts are suppose to be substituted. Running man cp to bring up the manual page for the

cp command gives the following three ways the cp command can be used

cp [OPTION]... [-T] SOURCE DEST

cp [OPTION]... SOURCE... DIRECTORY

cp [OPTION]... -t DIRECTORY SOURCE

We can see that this manual page is using capitalization instead of angle brackets to specify what parts are

suppose to be substituted with what they describe. From this we see there are actually three distinct modes in

which cp can run, and all three allow any number of the options (e.g., -a, -b, -d, -f, etc.) to be

specified. The first is when you specify only a source and destination file name, as in

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] mkdir example

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] cp -T flights-downloaded.zip example/flights.zip

This make a copy of the SOURCE file called DEST. We have provided the optional -T parameter in this

example. This doesn’t do anything unless DEST happens to exist as a directory. In this case cp will

provide an error instead of assuming you are invoking the second variant of the command.

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] cp -T flights-downloaded.zip example

cp: cannot overwrite directory 'example' with non-directory

Without this option, we would inadvertently invoke the second form of the cp command which copies one or more

files into a destination directory, as in

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] cp flights/0144f5b1.igc flights/2191bc99.igc example

The final is the same as the second except you specify the destination directory first

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] cp -t example flights/0144f5b1.igc flights/2191bc99.igc

again this is provided only to ensure you don’t accidentally invoke the first form when you really wanted the second form.

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] cp -t examplee flights/0144f5b1.igc flights/2191bc99.igc

cp: failed to access 'examplee': No such file or directory

One final nice feature of bash is that it has a history of prior run commands and does completion of commands and filenames. Pressing the up and down arrow keys will scroll through your previously run commands so you can edit and rerun them without having to type them all back in. Pressing the tab key partway through a filename or command will complete it up to the first ambiguity. Pressing tab key again will display all possibilities. For example

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] r<PRESS TAB TWICE>

Display all 158 possibilities? (y or n) y

ranlib reduce_test ...

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] rm -fr exa<PRESS TAB ONCE>

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] rm -fr example/

where we are abusing our angle bracket and capital notation to tell you to press the tab key. I would strongly recommend forcing yourself to use tab competition throughout this workshop as, once it becomes second nature, it will vastly improve the speed with which you can run commands.

Transferring files

The other use of the secure shell client programs is for transfer files. The scp (secure copy) command is

basically a version of the cp command where you can specify a remote computer as the source or destination. As

an example of this command, I will end my session on graham, which returns me to the command line on my local Linux

computer, and use the scp command to copy the /home/tyson/flights/0144f5b1.igc file from graham

[tyson@gra-login3 ~] exit

[tyson@tux:~]$ scp tyson@graham.computecanada.ca:~/flights/0144f5b1.igc .

Note that I’ve used . as the location to copy the file to, which means the working directory.

There are also many graphical applications, such as MobaXterm and WinSCP under Windows, that use the secure file

transfer protocol (sftp) in the background to let you simply drag and drop files between your computer. Most Linux

file managers also have this ability built into them and you simply needs to specify the remote path to accessing

using the special sftp://<user>@<computer>/<path> URL

You may need to setup your secure shell client with a secure shell key so it can login to graham without using a password for this work. See the Compute Canada documentation wiki for details on how to do this.

Linux and Mac OS X (if you install FUSE for macOS) also have the the ability to

splice a remote file system into your local file system using the sshfs command. For example,

[tyson@tux:~]$ mkdir graham

[tyson@tux:~]$ ls graham

[tyson@tux:~]$ sshfs tyson@graham.computecanada.ca:/home/tyson graham

[tyson@tux:~]$ ls graham

flights flights-downloaded.zip

This is quite powerful as you can then do anything you can do with local files on the remote files. Examples

include simply using the standard cp (copy) command to copy them to a local path

[tyson@tux:~]$ cp graham/flights-downloaded.zip .

or even directly edit them in your standard editor. Of course they will take longer to access though as they are

actually being transferred back and forth under the hood using the secure shell system. The fusermount command

with the -u option un-splices the remote file system

[tyson@tux:~]$ fusermount -u graham

[tyson@tux:~]$ ls graham

Exercises

Transfer some of the .igc files in the flights directory to your computer. Have a look at them in your text editor and view them in the online IGC file viewer. We will be using command lines tools to automate processing of these files shortly.

The

rsynccommand is very useful when working on multiple computers. An example of typical usage might be[tyson@tux:~]$ rsync -e ssh -auvP tyson@graham.computecanada.ca:/home/tyson/flights .

Use the

rsyncmanual page to describe what this command does.What advantage does

rsynchave over using-rwithscpto recursively copy all files and directories?Would it be easier to automate dragging and dropping new files or running an rsync command for weekly updates?